A Pair of Photos (2014)

A previously print-only essay on love marriage, partnership, and the mystery of the decisions our parents make.

Note: “A Pair of Photos” was originally published in the 2014 anthology, Salaam, Love: American Muslim Men on Love, Sex, and Intimacy It is being re-published here for the first time online. Endless thanks to Ayesha Mattu and Nura Maznavi for supporting my debut and to my father and mother for their story.

I. A Love Story, 1975

The day before they fly to America, Chacha and Raani marry in the living room of Raani’s childhood home. The party is small by Pakistani standards—perhaps twenty-five people. Of fiery, brave Raani’s family, the core is in attendance. The two junior sisters hover in plain shalwar kameez, colored dupattas thrown hastily over their shoulders. The two boys lumber in the corner, hands in trousers. It is a sober affair.

Raani’s father had threatened to cancel the wedding. Like many Pakistani men of his generation, he left centuries of tradition post-Partition. Prior to 1947, the majority of his clan had lived near a Sufi shrine in East Punjab. Violent sectarianism scattered that history throughout West Punjab. Given all he had lost, he hoped that his children would marry within the family as he had done. It was improper, he insisted, for Raani, a fine, Urdu-speaking descendent of sheikhs and the clan’s first child of Pakistan, to marry a country Punjabi like Chacha. Somehow he acquiesced, perhaps seeing the fire mirrored in his eldest daughter’s eyes.

Quiet, loyal Chacha was not so lucky. His family had also left their land and livelihood in East Punjab. But unlike Raani’s scholarly, urban ancestors, they were wealthy rural landowners who married others of their own caste. His sister and each of his five older brothers had married Rajputs of the family’s choosing. Chacha did not believe that Islam contained anything like “caste.” As the youngest, perhaps he thought he could get his way, but the discussion was short and uncomplicated.

“We do not approve and will not attend.”

Chacha did not attempt to convince them. It was the first time he had disobeyed his mother and elder brothers. In a version later told by Raani, Chacha was locked in a bathroom the morning of his wedding, broke out through the window, and took a bus to the ceremony. Chacha laughs and calls it a total fabrication—except for the bus part.

His family boycotts the marriage, including his beloved, widowed mother. Representing the groom’s side are three classmates and one of their fathers. All of them will later follow Raani and Chacha to America and become their surrogate family.

It sounds depressing, but Chacha smiles and laughs in every photo.

Raani, unusual for her, looks demure as a bride. She hadn’t had time to find an outfit for the wedding and wears a red lehnga from a recent Eid, adorned with her mother’s finest gold jewelry.

In Pakistan, a distinction is made between love marriages and arranged ones. Chacha and Raani did not have an arranged marriage but when asked why they married, their answer does not mention love. Instead:

“We were partners.”

They met during medical school in Lahore. Chacha’s older brothers were of different professions—engineer, politician, diplomat, army man and businessman. Chacha would be his family’s first doctor. Raani was following in the footsteps of her mother, an obstetrician. Her sisters and a brother would soon join her in the medical profession. For both, cosmopolitan Lahore represents an unparalleled adventure.

Chacha hangs with a crew of pranksters, the moral compass of the group. There are ten girls in their class of one hundred. Though Raani spends much of her time with those ten, she is the undisputed leader of boys and girls alike. For a long time before their meeting, Raani hears of a person named Chacha, and she is confused by this name. It means, basically, ‘uncle.’ She wonders who this Chacha is who could inspire such respect from the male medical students.

When she finally meets him, she is underwhelmed. He is a year her junior. She notices his well-pressed clothes, in contrast to his friends, who lounge around, wearing tank tops and lungis and smoking cigarettes. He notices her simple khaddar clothing and asks, “Why are you wearing that clothing?”

“It’s for workers’ rights. I don’t need anything finer than what they spin and wear,” she replies. “Here’s a better question, bhai. Why are you called Chacha?”

He laughs. “You’d have to ask the boys.”

“Surely you should know why you have such a strange nickname, Chacha.”

“You can just call me Waheed.”

“I’m Raani.”

Chacha’s friends become Raani’s friends, and Raani’s become Chacha’s. As a group, they scribble and share notes, hike in the Himalayan foothills, drink chai and eat pakoras at truck stops, mock their professors’ English and discuss the unmatchable poetic genius of Faiz Ahmed Faiz. Soon, the boys send food from their mess hall to the girls’ dormitory—the girls’ rotis were stale and their daal watery —along with flowers and sweets.

Raani scoffs at the flowers from Chacha, but she is softened by the fact that every time he sends them, he sends a bouquet to her younger sister too. She also finds it strangely endearing that during finals Chacha grows a beard and proceeds to pull hairs from it until a dime-sized hole appears on his chin.

In Chacha, Raani sees someone with competence and a work ethic that can support her revolutionary, feminist ambitions. The two are enamored with the struggle of communist revolutionaries in Latin America and the Muslim world. They debate among their friends the role of Islam in such struggles. Chacha shares the bonds he made with Muslims in Africa and the Middle East, making a convincing argument for Islam’s capability to unite.

By the time they graduate, the friends have decided to go to America. The opportunities are better, and anyway, they plan to return—someday. After she graduates from medical school, Raani announces to her father that she is going to America and that she and Chacha want to get married. After a year trying to convince her father, she succeeds. They arrive in snowy New York the day after their marriage.

Initially, there are issues.

Raani is the epitome of her family’s analytical, emotional, and lighthearted characteristics. Chacha’s family is hardy and upright, leaving painful emotions unspoken. In many senses, Chacha is the exception to his patriarchal family. His home was intergenerational, with his brothers’ families living in the same compound. Chacha respected his brothers’ wives for their quiet forbearance, and his mother for her capabilities as a single mother.

But still they both have difficulty adjusting to married life. Chacha struggles with his role as man of the house with a wife who was raised in a household where the woman was the breadwinner. Raani always wants to discuss relationship issues; Chacha would rather let them lie. America is demanding and lonely and it takes them time to reestablish their partnership.

When she finally meets Chacha’s family in Pakistan a few years later, she swallows her anger at their rejection. They treat Chacha normally, but Raani does her best to charm them and fit in, especially by spinning stories for the children. Slowly, Raani grows to become an essential part of Chacha’s family. By their middle age, Chacha and Raani have become specialists in surgery and immunology, respectively, and leaders in the Muslim, Pakistani American, and medical communities. They have three overanalytical children—two girls early on, and then, after a period of eight years, a boy. Chacha and Raani do not teach their children to expect arranged marriage. There is an expectation that their children will marry Muslims, though not necessarily Pakistanis. Raani’s allergy practice allows her to come home early. She prepares the delicacies of her childhood—rice cooked in lamb broth, delicate kabobs, and eggplant in yogurt—as well as Chacha’s favorite, daal and rice. The children yearn to spend more time with Chacha, who leaves for surgery before they wake up and comes home exhausted, sometimes spending entire Saturdays catching up on sleep. The children pursue careers in service, human rights, and academics. Raani and Chacha are disappointed, but have a hard time arguing against their passions. Finally, the children leave for work or school. Chacha and Raani argue a little less and talk a little more. Their time is spent working toward a lifetime goal—building a masjid for their once-small midwestern Muslim community. Things are good.

They have two years of this.

Then, Raani is diagnosed with cancer. Her body reacts poorly to her treatment. She battles with illness over two grueling years, and dies in her home in the presence of Chacha, two of his siblings, four of her siblings, all three of her children, and a few cousins. It is the day of their wedding anniversary, and loyal Chacha left work before noon to bring home flowers, as he has done every year for over a quarter-century. I, her youngest, was twenty-two years old.

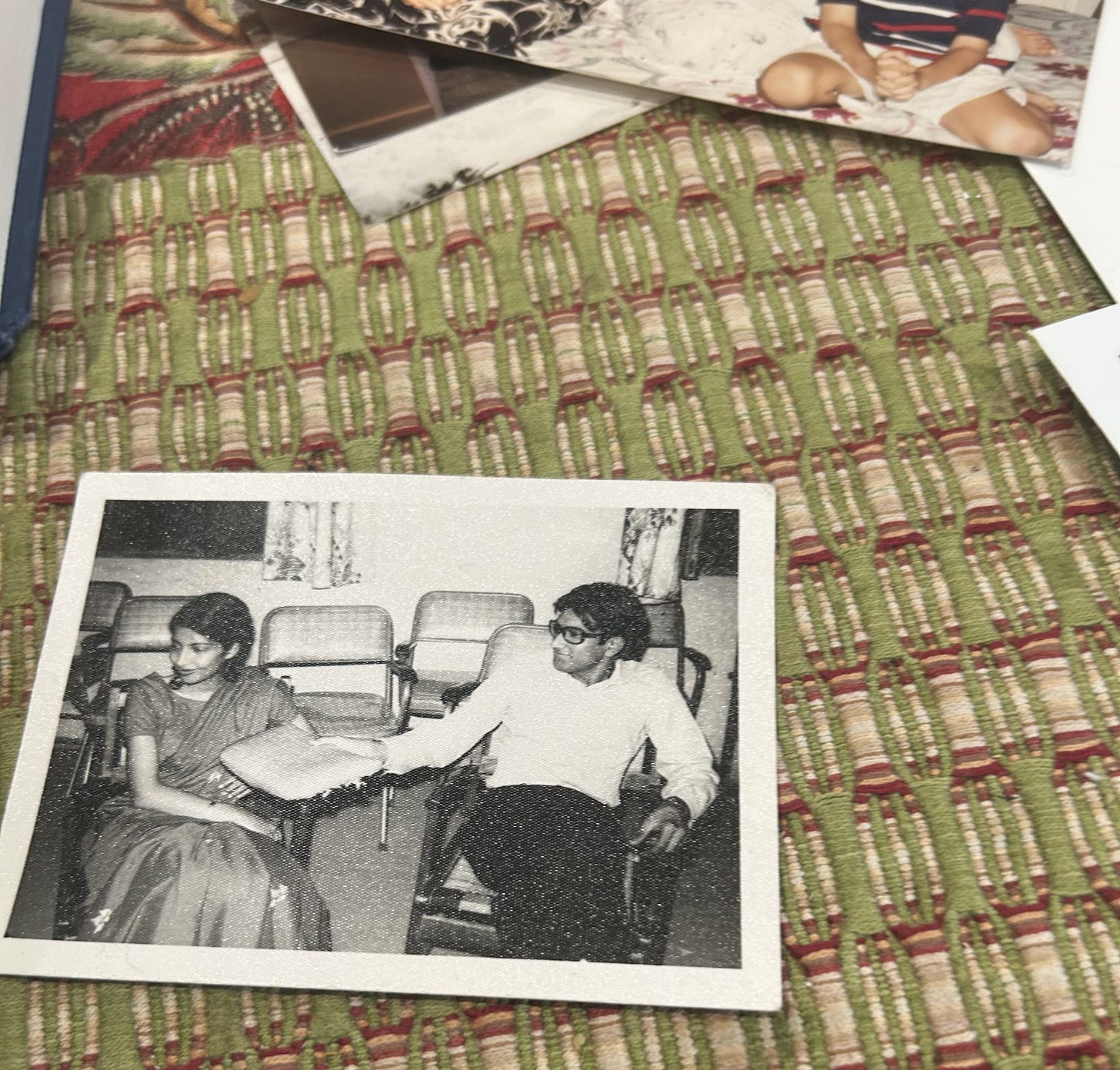

II. A Set of Photos

I know Raani and Chacha’s story because Ammi told me herself. As the oldest of six and a voracious reader, she found that telling stories was the best form of entertainment for the young ones. They gathered around her, listening to Api’s grand tales with rapt attention. She later gave my sisters and me a romantic, detailed account of her life. I have always struggled to understand what my father was like before he married Ammi. Like many men of his generation, Abu categorically refuses to speak about himself. My mother, ever the storyteller, provided much of the perspective we had on our father.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Rad Brown Dads 2.0 to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.