The many contradictions of the khadi suit

An ancient, irregular fabric shaped by resistance collides with one of the most codified garments in Western dress.

I’m proud to debut the first of a three part reported series on khadi, a natural fabric with roots in the Indian subcontinent. This piece, as well as most future journalistic works, is available for free. Paid subscribers, however, fund my ability to report, document, and pay contributors for features (in addition to access to paywalled newsletters, guides, and updates). So if you’re reading this for free, please consider becoming a paid subscriber so I can continue working as an independent journalist. In January, I’m looking for 25 new paid subscribers to make my next story possible.

As I sit with a cup of tea in his kitchen, Moeen Lashari hands me piles of sample shirts, pants and Western-style suits from Pakistan. It’s a demonstration of the expanded tailoring offerings his company, the Post-Romantic Co., launched in 2025. With his thick glasses and flowy salt-and-pepper hair, he rattles off details with scholarly ease. The construction: done by careful hands of single craftsmen. The fabrics: evergreen wools, seasonal classics like corduroys and linen, and an eclectic range of cottons, all produced by well-regarded, "small family-owned mills” in Europe and Asia. The style: two-buttoned, natural suits, in a style Lashari dubs “Lahori-British.”

“It’s basically what the tailors did in Naples,” Lashari said. “They took the English suit and then they started taking out the padding to make it easier for the wearers in the hot climate of Punjab.”

It is, undeniably, fabric heaven. But I didn’t drive to upstate New York for a collection of classic suits. I came looking for a garment made from a fabric historically positioned against industrial uniformity.

A tailored suit made of irregular khadi.

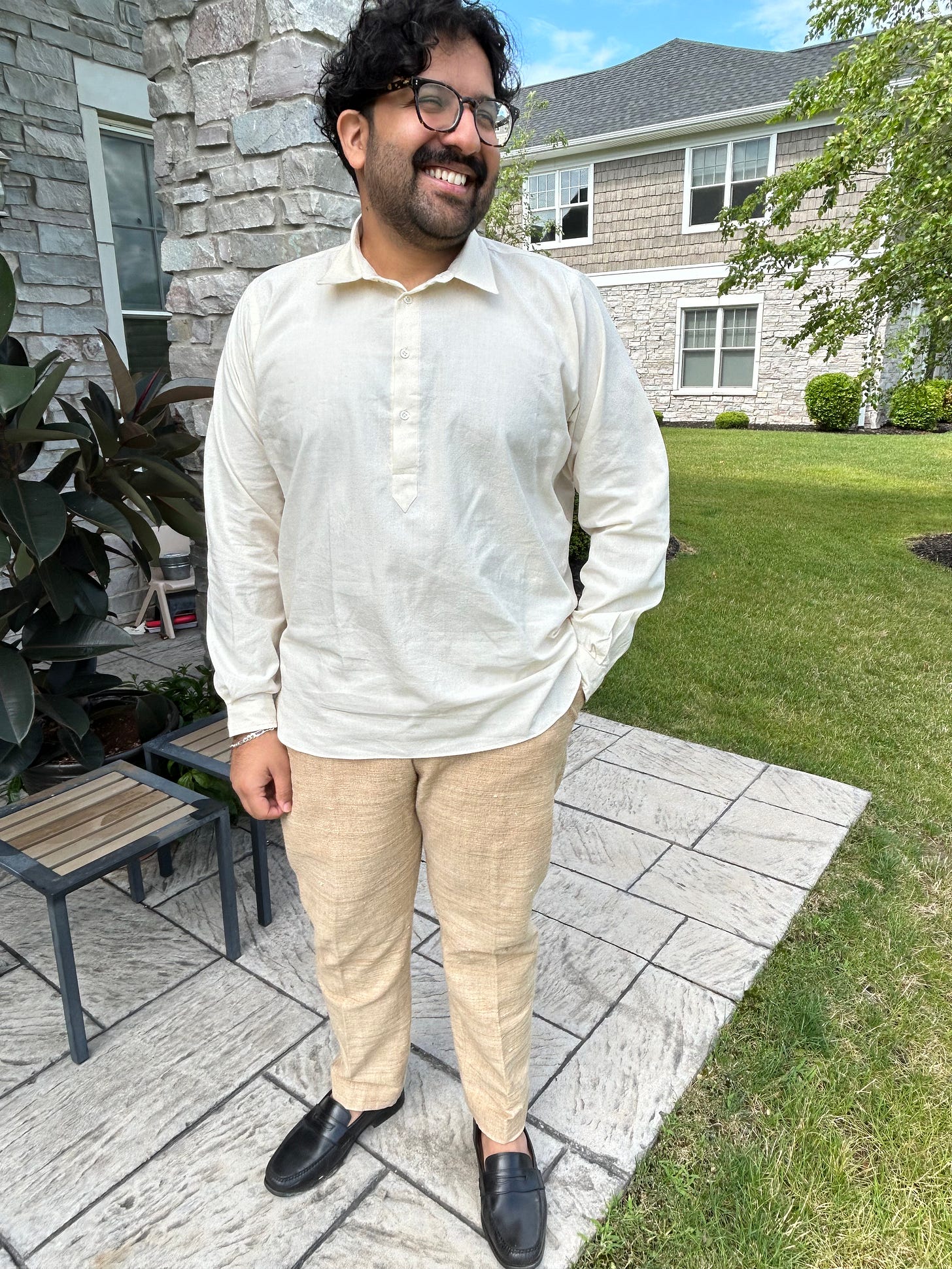

“It’s the most ancient type of fabric done in Punjab,” Lashari said as we ran our hands over the bumps, specks, and twirls of irregularity dotting the fabric. Post-Romantic has for a few seasons offered khadi in oxford-style button-downs, trousers, and popovers, but I’d never seen it in a suit before. It’s woven in a plain weave that varies in density, texture, and pacing. Up close, it’s like gazing at rows of hand-planted bushes or rolling hills from an airplane window.

The political and cultural contradictions of the garment loom large. The business suit is a symbol of Western colonialism and the colonized elite who adopted Western mores. Khadi, on the other hand, became an anti-colonial symbol as the centerpiece of a 1918 campaign by Gandhi to promote self-reliance against British industrialization.

In the United States, the suit is a uniform of a bygone era of the corporate workplace and in many South Asian countries, handloomed fabrics are a symbol of the laboring class. Tailoring emphasizes clean lines and smooth fabrics, while handlooming, which defines khadi, is irregular and inconsistent (sometimes described as “slubby”) in a way a machine can’t duplicate. On the Post-Romantic suit, the fabric is so raw that whorls of plant matter puff out from the garment and the color varies between batches depending on the cotton’s natural hue.

Derek Guy, also known as the internet’s “menswear guy,” often argues that dress is a form of social language. Natural, small-batch, minimally processed fabric and clothes have had a history long before our current microplastic hellscape.

In particular, khadi has a complex social and political role in the Indian subcontinent. In Clothing Gandhi’s Nation: Homespun and Modern India, Lisa Trivedi writes that though spice may have brought traders to the Indian subcontinent, “it was her cloth, and eventually, her cotton which figured so significantly in India’s colonization.” Indians, known for their handmade textiles, were soon dependent on British industrialized fabrics, which was why the 1918 khadi movement was characterized as an anti-imperial movement of indigenous self-reliance. Gandhi may have popularized handloomed cotton’s political significance, but he didn’t monopolize its meaning. Trivedi explains that, in the 1920s, khadi already began to become a broader, enduring symbol.

The khaddar items I’ve purchased from Post-Romantic previously to this story were easy to wear and incredibly affordable. I picture them adding a subtle, texture-forward desi insouciance to my closet. Specifically, I bought popover shirts, which echo Pakistani kurtas while still reading easily as American casual clothes. The fit was good enough that I’ve ordered more since the initial purchase. This particular khadi cotton was a lighter weight with a beautiful texture.

Suit fit and fabrics are a whole different, more challenging beast. The particular makeups Post-Romantic debuted for tailoring bring to mind certain images of social life. For fall, a structured brown corduroy from the U.K.’s Brisbane Moss is professorial and dapper. For the summer, a blue linen suit from Italy’s Solbiati conjures strolls on the Mediterranean.

What then, are the referents and cultural meaning of khadi, this deeply anti-colonial fabric, in a Western suit? In what contexts does one wear an undyed, natural cotton suit? What does it signify about the wearer? And will it find a place in men’s style?

Khadi, also called khaddar, is closer to a process, though it has come to be associated with a particularly roughspun cotton fabric used for kurtas. Technically, wool and silk can be khadi and so can chambray, corduroy, and other fabrics.

To understand what makes khadi unique, it may help to compare it to khaki, a term that comes to English from the Hindustani word for the color of soil or dust. In the parlance of men’s clothing, a “khaki” is a beige trouser woven in a tight, diagonal twill. The associated fabric is defined by its British, military uniformity. To achieve that finish, the cotton must be ginned, mechanically spun into yarn, dyed, woven by industrialized machines, and made into fabric rolls before it’s cut and sewn into a piece of clothing.

You could, theoretically, make a handloomed khaki pant, but the khadi-khakis would have flecks of black and white from the unprocessed seeds on the surface, the usually rigid diagonal twill would be broken into uneven lines of varying thickness, and the weave itself would be looser. That’s because, when all of the processing of the fibers is done by hand, it’s impossible to maintain precise tension, torque, and force like a machine could.

As an aside, I have not personally witnessed the steps of handlooming, but I’ve reviewed videos from Post-Romantic, 18 East (see below), and other clothing manufacturers from their partners in Pakistan and India. Jamil, one of Post-Romantic’s tailors in Pakistan, told me over WhatsApp video that they purchase their khaddar from the city of Kamalia, which is one of the most famed sources in Pakistan for handloomed fabrics.

In the States, Indian khaddar has become well-known amongst a certain strain of heritage-obsessed menswear enthusiasts. The kind of people that a decade ago pined for the obsolete era of American-manufactured raw selvedge denim are now digging into a parallel heritage workwear fabric. In 2022, GQ declared, “Old World Indian Fabrics Are Going Global.” In part 2 of this series, I’ll be exploring how brands like 3Sixteen, Karthik Research, 11:11 and 18 East have aligned khadi with values of slow fashion, natural fabrics, and transparency in manufacturing.

For the most part, these brands do not offer the kind of khaddar suit that Lashari offers and none of them work with Pakistani fabrics or artisans.

Post-Romantic’s khaddar suits currently cost $450, and heavier suits from other mills cost about $750. Structurally, the suits are constructed with a few details that are usually only available elsewhere at a premium, including canvassing options, side tabs, and functional buttonholes on the sleeve. One of Lashari’s broader aims is to shift negative perceptions of Pakistani quality by training a team of independent tailors to make suits for Western clients and providing them with high quality fabric. The process, he said, has been difficult, and consistency remains a work in progress. But the skills are there.

“This is exactly what Kiton does,” Lashari said, showing the canvassing and layers of a lined suit. “Most people just fuse it with glue.” Not all suits are canvassed, but when they are, layers of horsehair and goat hair (especially in the lapel) give structure and help the suit mold to the wearer. It’s the traditional method, largely abandoned decades ago as factories replaced artisans.

The standard option at influential men’s shops like J. Crew, Suit Supply, and Spier & Mackay is half-canvassing. In a half-canvas suit, fabric is still layered in the lapel area, but the other parts of the suit are still fused. You might be able to order full canvassing for an upcharge, but even then, the suit will be done with less hand-work and the fabric may also be a synthetic blend.

So if Lashari’s tailors can execute, they’re providing a level of craft that is exceedingly difficult to find in America at an incredible price point. And because a single tailor is making the garment, there’s significantly less waste. Personally, I’ve been looking for a way to work with tailors in Pakistan on Western clothing for nearly my entire life; now, finally, I have the means to do so, even if it’s all done by the internet.

Lashari didn’t come from a family of tailors. The idea of Post-Romantic came to him when he was working in Manhattan. Lashari himself would often receive packages of clothes from his family in Pakistan — his non-desi friends and colleagues would marvel at the quality. When he worked at the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), he saw poverty alleviation programs that tried to teach agri-business in Pakistan. Rather than training new skills, Lashari thought there was an untapped market of using tailors for a Western market.

The tradition of tailoring has survived in Pakistan because families pass down skills to their children. While urbanization and UNDP programs might take family members out of the house and into the city, Lashari believes growing the tailoring market while increasing pay and volume of sales would allow some Pakistanis to build economic stability from the comfort of their home. All while preserving a centuries old craft.

Over the past two-and-a-half years, Lashari has cultivated a network of tailors. Often trained in a lineage of a master tailor, they sometimes bring to him underutilized family techniques, including blockprinting. He claims the level of expertise is so high, that even if someone like Jamil had never made a Western-style suit before, he could pick it up on the first try. Lashari simply had to provide the pattern and guide them towards a certain style. In at least one case, a tailor added an unasked-for splash of flash: paisley cuffs intended to flip up, Amitabh Bachchan-style.

“It’s a slight redirection of what they’re doing,” said Lashari. Before the new suits debuted, he took the time to train them in a group so that any item of clothing from one tailor or another would be the same. He is stepping into an existing work flow of people who are making clothes for local Pakistanis while still expecting some consistency.

Because Pakistan is roughly 10 hours ahead of the U.S. East Coast, Lashari often takes business calls after 9 p.m. Eastern, as tailors in Punjab begin their workday. There, full-service tailoring remains common, especially around holidays like Eid, when customers collaborate directly on custom designs... often leading to delays for Post-Romantic, since Lashari does not have exclusive access to tailors. As ready-to-wear clothing has expanded its share of the market, many skilled craftspeople are now seeking additional work.

While there’s a practical idea of employing tailors in Pakistan, Lashari also has visions of “meaningful sustainability” and accessible taste. He describes the village he grew up in as a place with a system of communality, where clothes are indispensable, made one at a time, and always passed down.

“That sophistication goes to a very deep level,” said Lashari. “All these people dressed really well.” There, even those who can’t afford the best fabrics have an eye for texture and fabric quality, because of the textile culture.

In addition, Lashari is a proponent of fit above all. While you could order stock S-XL sizes from Post-Romantic, the default is to send your measurements over and hope for the best. My own experience has been solid — I’ve paid for all my clothing and only one pair of pants required a remake. The main issue for me has been delays — you’re working with individual craftspeople, after all.

That night at Moeen’s, I had only a precious few moments holding the khadi suit. I decided to order the same one to get more hands-on time.

I paid a local tailor $10 to take my measurements, ordered my item on the website, and waited.

In the meantime, I had more khadi to see in the Lower East Side of Manhattan.

Part 2, The American Khadi Movement, will be published on January 22nd. Part 3, on the khadi suit I purchased for my father, will be out in February.

Credits

Edited by: Hajar Ouahbi and Sal Tamarkin

Photos and Visuals: Asad Chishti

Additional reporting: Waheed Akbar

Lovely piece ! Loved working on it. And looking forward to the next parts hihi 🤭🤭🤭