On the road with Punjabi truckers and halal goat

Back to independent writing, I don't know what's next. I plan to keep moving.

House-keeping note: I am enabling payments with this debut post; please consider subscribing! My hope is my audience will consider it an investment in my writing and future ability to pay editors and photographers. If you pledged to support this Substack and your financial situation changed, please let me know.

In a near-empty gas station on the Pennsylvania Turnpike, I’m eating halal goat curry cooked by Sikhs as devotionals to Christ play along on the radio.

🎙“Jesus, all I want to do is be like you.”🎸

Behind me, the few other customers are gambling on two-top machines. Outside, a dozen or so Tesla charging stations stand empty. 18-wheelers and their drivers rest in the shadows. In the parking lot at Sardarji Da Dhaba, where I purchased this meal and concluded a 12-hour road trip from Michigan, there’s considerably more activity. Blinding lights illuminate the yellow food truck, advertising veg and non-veg options. Men scroll on their phones as they wait for food orders.

And here I am, a newly unemployed food and culture writer with a story in front of me and nowhere to publish it.

I’ve known for some time that Punjabi truck drivers have been transforming the highways of America (to say little of the longer history of Punjabi Americans1). An oft cited stat from 2019 estimates about 150,000 Punjabi Sikh truckers working in the United States.

Raman Dhillon, the CEO of the North American Punjabi Trucking Association, said that he frequently gets asked to put a number on his community, but it isn’t easy to document.

“There’s no set number on it - (150,000) is just an estimate,” said Dhillon. “There’s probably a lot more than that. After COVID, a lot more people came into industry.”2 Dhillon himself has worked in the trucking industry since 1996, though he gave up driving in 2013. Dhillon and NAPTA are based in California, a major site for Punjabi Truckers, and boasts about 2600 members, according to Dhillon. Their Instagram, Punjabi Trucking USA, described as a magazine and featuring a podcast, has over 12,000 followers, though on a short look, engagement seems low.

For Punjabis, the “dhaba” is a romantic kind of thing, sort of like the 24-hour diner. They’re street-side eateries that are full of character, affordable and delicious. I’ve had my fair share of dhaba experiences in my travels through India and Pakistan. In the 90s, weaving through the Himalayan mountains, my family would have some of the most unique culinary experiences on benches sitting steps away from a sheer drop off of a mountain.

Interestingly, in recent years in Pakistan, significant infrastructure expansions have happened as a result of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Once, where travelling from Lahore to Islamabad might have had bathroom stops, now there exists well-maintained, consistent rest areas with a wide variety of options. In my limited experience, the dhaba element is almost nestled in as an afterthought.

Here in Milton, Pennsylvania, was my first experience in a real life roadside dhaba in my home country. I picked Sardarji da Dhaba because of it’s clear Sikh identity and usage of Punjabi language. “Sardarji” is an honorific used for turbaned Sikh men (which, it’s important to note, can also be used in a derogatory manner). However, it became clear immediately that part of the social function of this dhaba was to provide dietary variety to truck drivers of all different backgrounds, including Hindus and Muslims.

All I was able to eke out was “whoa, goat curry?” before the be-pagri-ed young man taking my order informed me it was halal. It was refreshing to see the competing, also-classically Indian value of inclusion against communalism. Of course, it was; Sikh’s are well-known for their egalitarian, free kitchens known as langars.

There are some unique challenges reporting on South Asian food as a South Asian. Food given in charity is such a core value and frequently that I have to aggressively refuse free food. One family member told me of a free paratha at another dhaba. But thankfully, they let me pay.

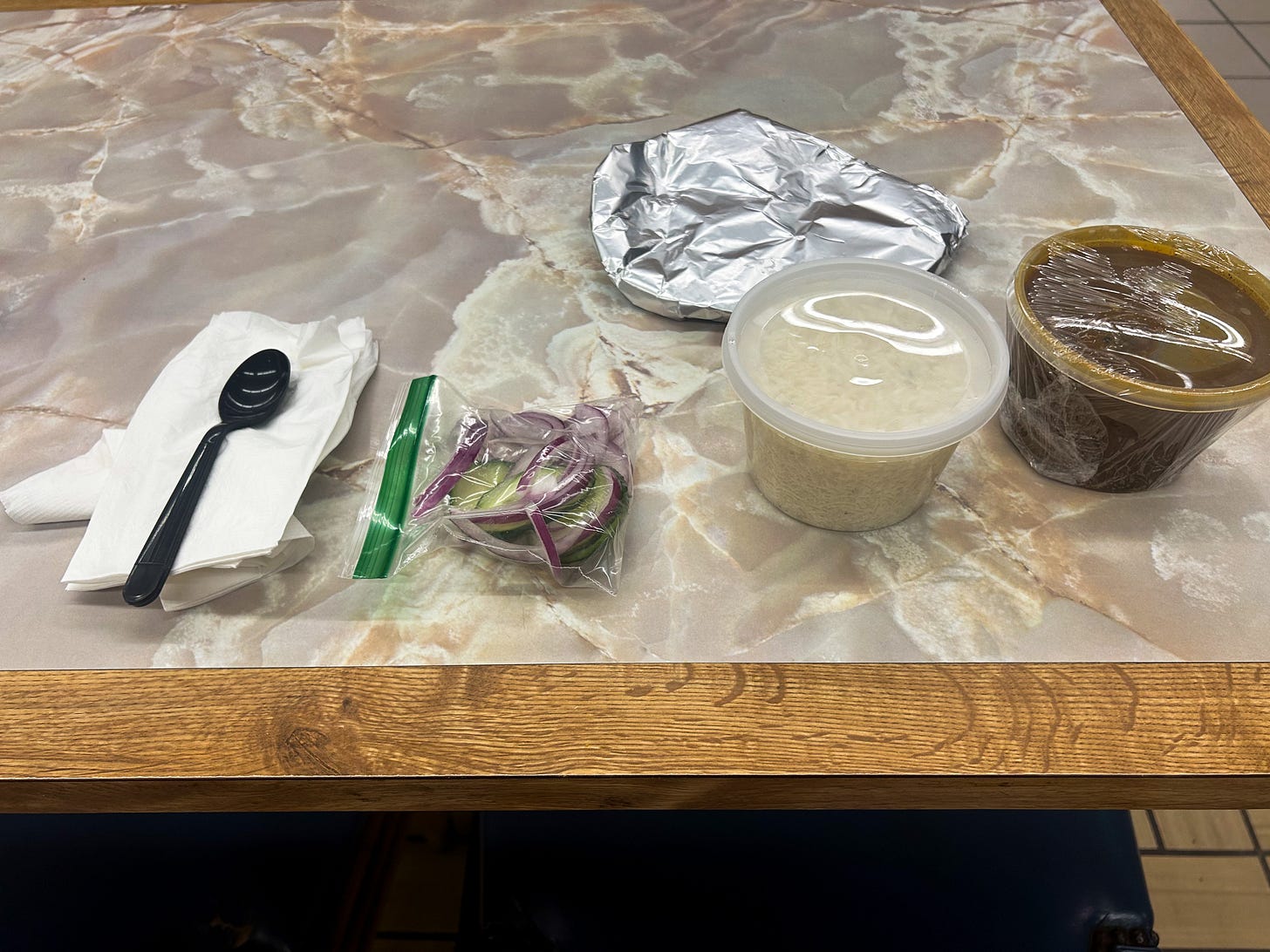

Despite the dhaba name, I was expecting something within the gas station, the way you might find a Subway or Dunkin. Instead, when I pulled in, I found a secondary ecosystem in the parking lot.

I was on this trip to New York in order to meet with my peers at Acacia Magazine. Since the first issue, I’ve been an editor at Acacia working on stories of culture, history and reporting from the perspective of the Muslim Left. I had been struggling and struggling to launch this damn newsletter. With that plate in front of me, I began taking notes and decided, it’s time.

For me, writing is like getting blood from a stone. Reporting, on the other hand, is seamless. I am an extrovert reporter, one who loves thrusting myself into new situations. But pitching has always been the biggest stop gap; I know from conversations with others what makes a story. And I’ve always sold my writing, never finishing it for anyone but an editor. I don’t always know what my piece will be until I sit down to write and rewrite and rewrite. I know it’ll be good.

But things have to change. As lay-offs, the economy and government intimidation ravage journalism, I know that this industry can’t always sustain me. My pace is a liability. But, I’ve learned, people still want to read what I write.

And so I’m trying to be a reporter on the road. Someone who takes the long routes and the shortcuts.

This Punjabi dhaba felt like a perfect encapsulation of the new kind of writing possible by sending it to my readers directly.

This isn’t a newsletter. This isn’t a food blog. This is a place to work on craft, in conversation with sources and readers. I don’t know what’ll come of it, but I hope you’ll consider becoming a paid subscriber so I can spend an hour at a roadside stall and order extra food.

Back to the dhaba.

Needless to say, this was the first time I had goat at a gas station in the U.S. For me, the classic dishes one wants to eat off a stall are the heat-kissed pakoras and buttered parathas, things that demand to be eaten immediately. Goat, meanwhile, needs time and energy.

This goat had been given what it needed. It gave way with ease and tenderness, even as I used plastic forks. On a sensory level, it hit all the marks of spice and heat. The roti and rice were functional, effective compliments to the meal. Onions and green peppers mingled in a plastic bag; together, they brought down their respective intensity.

I went back out to speak to the chefs and to order a chai. The shy man taking my order said he thought the truck had been operating for about two years.

They were too busy to talk then. In my usual reporting, I’d follow up with a call. I almost considered skipping the step, but right before publishing, I cold-called and got to speak with Gurmel Singh, the owner. When he picked up the phone, there was a storm of background noise, of clanging metal and Punjabi.

“We specially opened for people who drive the trucks, but now we get local traffic a lot,” said Singh. He himself drove a truck for a few months in 2022.

The dhaba name was intentional, he told me. To advertise that it was Punjabi food of a certain genre that appealed to truckers.

“It’s not like restaurant kind of food - it’s like homemade food,” said Singh. “…People who are trucking, they don’t want too much spices or masala. They want regular homemade kind of food. For the digestion.”

It’s clear that he’s well attuned to the diets of his customers. Most of them are Punjabi truckers, but occasionally cars pull up of customers from states like Gujurat.

“Many people from India, they are vegetarian,” said Singh. “I have more items in the vegetarian menu than non-veg.” He started listing out the classics. Saag. Shahi paneer. Mattar paneer. Punjabi chole. Daal tarka. Daal Makhni.

South Indians, he mentioned, might have some restrictions on onions, ginger and garlic, but by advertising himself as Punjabi, he can let them know that the food might have some of those ingredients they avoid.

These dhabas are stories in each community, growing and changing in their context.

Speaking of a dhaba in Vega, Texas, reporter Meena Venkataramanan describes how the only Indian residents of that town are the business people who offer food and board, amongst the 1,000 residents.

Initially, Arjot Sandhu and his family started a typical truck stop with American snacks. But, Venkataramanan writes, they discovered the Indian trucking demographic.

“As they began to see more Indian customers come in, they started asking them what they’d like to see in the store.”

This story is replicated across highways in the United States. This story for me began when I remembered Venkataramanan’s stories3 and on a whim simply googled Indian food on my route. Good reporting can do that.

Venkataramanan has herself made an unffocial Google map to Punjabi roadside dhabas across the U.S. Sardarji da Dhaba is not yet there, but I’ve made contact with her to discuss.

I had an embarrassment of choices, each with stories of their own.

After I left, I arrived in New York, where I decided I'd continue my practice of reporting in movement, grabbing stories as they come. Substack had been waiting for me to write some time. I’d drafted guides and intros and house-keeping posts. But rather than hemming and hawing, I just started doing what has become the bread and butter of organizing. Going out and talking.

I’ll start this by making these little stops. This will not only be a food blog, but over the next few weeks you can expect stories on the following:

Nyonya in Manhattan Chinatown (alongside a guide to Rad Brown DadsNew York City Eats)

the Pakistani chopped cheese from Nishaan and a crossover moment for young American-Pakistani chefs in New York City

the Yemeni restaurant, Sheeba, in Michigan and the odd story of their Trump endorsement, alongside a guide to Michigan eats

I also plan to do long-form reporting as I did in my most recent job. Here’s a hint of what I’m working on.

It feels good to be on the road now. Both: in a writerly fashion and, you know, literally.

I’m sure many of you have questions about this platform, what’s next for me, and food recommendations. Feel free to leave questions by using the chat function here, DMing me on Instagram or Twitter (@radbrowndads everywhere) or leaving them in a comment below. I’ll choose a few to answer in a future Q&A post.

And as someone who writes too much, I’m experimenting with footnotes here to include sections I cut. Who knows if that’s a thing I’ll keep doing.

In a previous life, I was a student of the history of American Muslims and South Asians. What I learned then was that Punjabis, and in particular, Sikhs, are one of many migratory groups that have had longer roots in the Western Hemisphere than popular history depicts. Like the Chinese migrants who established the earliest Chinatown in San Francisco in the 1850s, Punjabis found their own community in the Southwest, working on as agricultural laborers and marrying Mexican women. In the South, Vivek Bald’s book Bengali Harlem talks of turbans as a recognizable symbol of eastern peddlers and merchants; some were, of course, Indian, but there is evidence that Black Americans too adopted these identities as a parallel, perhaps more protective identity in the context of Jim Crow. The “truck driver” is a well-known identity in America and one in which Sikhs could inject their own particularities and shape history, just like the migrants before them.

Punjabi drivers have been in the news recently, after a crash in Florida killed 3 in August. The Trump administration began questioning licensing, language requirements, work permits and immigration status for Punjabi Truck drivers.

Speaking of the current moment, Dhillon of NAPTA said, “people who can’t speak English much, they’re scared. They’re avoiding going out of California or outside or they’re getting out of trucking altogether even.”

Some more from Meena Venkataramanan.

“Vega is home to fewer than 1,000 residents, the vast majority of them White. The town’s claim to fame is its location along the historic Route 66, which accounts for most of its seasonal tourism.”

“The town’s only South Asian residents are the truck stop’s Punjabi owners and employees and the motel owners across the highway, who are originally from Gujarat in western India. Originally from Moga, a city in central Punjab, the dhaba’s owner, Beant Sandhu, wears a dastaar (turban) and grows out his beard in line with the Sikh tenet of kesh.”

“In 2018, the Sandhus started a truck stop in Vega. At first they stocked the convenience store with typical American snack fare: potato chips, soft drinks and candy. But they soon discovered that the trucking demographic is “actually more Indian,” said Arjot, than the family had initially thought, and a friend told them about the concept of dhabas along major U.S. highways. As they began to see more Indian customers come in, they started asking them what they’d like to see in the store.”

Yay! Let’s go.

That's interesting about the turbaned peddlers-- reminded me of the one in Oklahoma!-- and the fact of them often being African-Americans posing as South Asians made me think of the legendary Korla Pandit.